Biochar Beyond Borders - Thailand Biochar Sector

A comparative blog series across the globe

Why Thailand?

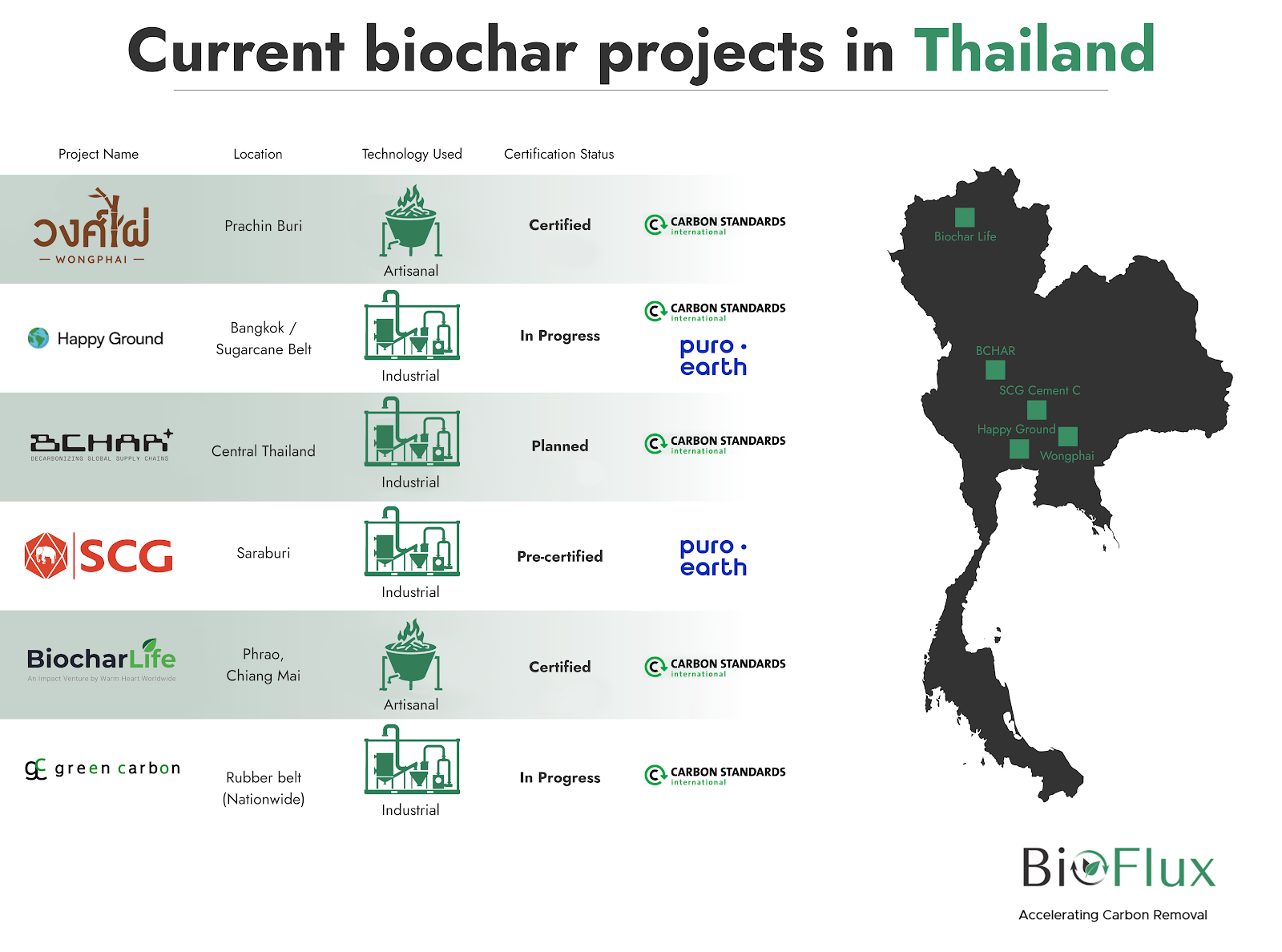

Thailand is quickly becoming one of Southeast Asia’s most dynamic frontiers for biochar innovation. Once a quieter voice in the global carbon removal space, the country is now gaining recognition through a surge of grassroots and industrial activity. From smallholder-driven systems like Wongphai, to scalable ventures like BCHAR and SCG Cement’s biochar-concrete pilot, and insetting pioneers like Happy Ground, which integrates biochar into corporate sugarcane supply chains, Thailand is shaping a model of climate action rooted in agriculture, led by entrepreneurs, and increasingly connected to global carbon markets.

Driving this momentum is the recent launch of the International Biochar Asia Pacific Trade Association (IBAP), co-founded by Thai entrepreneur Khomchalat Thongting. IBAP operates as a non-profit platform focused on expanding biochar’s role in sustainable development by fostering cross-sector collaboration, supporting applied research, and accelerating industry adoption across Asia. With its four-phase strategic roadmap, IBAP positions itself as a key node in advancing biochar as a solution to critical regional challenges, ranging from soil degradation and carbon emissions to waste management and green economy development.

We'll examine the broader dynamics of Thailand’s emerging biochar ecosystem in the following sections:

1 - Market Strengths in Thailand

Thailand’s biochar sector is gaining traction, driven by pressing agricultural issues like soil degradation and waste burning. The country has abundant, year-round biomass resources such as coconut husks and bamboo. Support is growing across farming communities, NGOs, government, and private sectors.

2 - Market Barriers in Thailand

Adoption is slowed by policy gaps, limited awareness, and skepticism from farmers uncertain about long-term benefits. High upfront costs and poorly suited imported technologies are major obstacles, especially for smallholders. Biochar also lacks recognition in Thailand’s carbon markets, limiting financial incentives.

3 - Market Integration in Thailand

Grassroots efforts and small-scale kilns lead current adoption, while technologies like Pyrovine aim to scale up sustainably. Applications are expanding beyond agriculture into construction and animal feed. However, the absence of national standards makes certification expensive and difficult for smaller producers.

4 - The Future of Biochar in Thailand

Thailand aims to become a regional biochar leader by investing in scalable technologies and building supportive policies. Raising awareness among farmers and officials is seen as key to growth. Developing local supply chains and knowledge-sharing networks will be crucial for long-term success.

In this edition of Biochar Beyond Borders, we had the privilege to speak with Khomchalat Thongting, BCHAR, represented by Nadja Oswald & Darius Stulz, and Happy Ground, represented by Pearl Pattamaphon Dumnui about the Thai biochar sector;

Khomchalat Thongting began his career in the IT sector, gaining international experience across more than 30 countries. In 2017, he transitioned into outsourcing, where he discovered a promising green opportunity within the bamboo industry. This led to the founding of Wongphai in 2019. Since then, Khomchalat has travelled extensively throughout Thailand, building a network of like-minded individuals and advocating for the potential of biochar. He is also a co-founder of the International Biochar Asia Pacific Trade Association (IBAP), a regional coalition supporting the advancement of biochar in Southeast Asia.

We were also honoured to speak with Darius Stulz and Nadja Oswald from BCHAR. Darius is the co-founder and CPO at BCHAR, while Nadja serves as Head of Growth. BCHAR is dedicated to scaling carbon removal by making biochar production more accessible, efficient, and impactful. With a strong passion for climate technology, Darius and Nadja bring a diverse background in data research and software engineering to their role, driving innovation and strategic development within the sector.

Thirdly, we had the opportunity to collaborate with Pearl, co-founder of Happy Ground. Their mission is to combat climate change through biochar and regenerative agriculture. By turning coconut biowaste into biochar, we support Thai farmers to transition to regenerative farming, enhancing soil and crop vitality.

Thailand's Strengths

While Thailand's biochar industry remains relatively nascent, it is gaining momentum, supported by key regional advantages and growing interest across sectors.

Agriculture remains a cornerstone of the Thai economy, representing 6% of its GDP andemploying one-third of its labour force1. Persistent challenges such as intensive biomass waste burning, declining soil fertility, and heavy reliance on chemical fertilisers create fertile ground for biochar adoption.

Khomchalat highlights biochar as a timely, practical solution to these issues. Biochar empowers farmers with a sustainable and cost-effective alternative by improving soil health, reducing fertiliser dependency, and enhancing crop yields. As climate change accelerates extreme weather events, the demand for long-term soil resilience strategies rises, further reinforcing biochar's relevance.

Thailand’s agricultural landscape comprises both large-scale industrial farms and smaller artisanal operations. Though their motivations differ – larger farms usually have the capacity to transition towards more sustainable practices, whereas smaller farms have to prioritise farm productivity, both have compelling reasons to adopt biochar.

Picture 1: BCHAR - current waste management

One of Thailand’s other key advantages is its year-round availability of diverse biomass feedstocks, including bamboo, cassava stems, and coconut husks. Darius and Nadja point to the megatonne-scale carbon removal potential of abundant materials like coconut husks. However, they also note that feedstock sourcing can be challenging due to the fragmented nature of agricultural production across the country.

Picture 2: Wongphai biochar application

Despite legal restrictions, open burning of agricultural waste remains widespread, contributing significantly to air pollution and public health risks. Weak enforcement allows these environmentally harmful practices to persist. In this context, both Khomchalat and the BCHAR team see biochar production as a scalable and sustainable alternative for managing agricultural residues while addressing Thailand's air quality crisis.

Interest in biochar is expanding beyond agriculture. Projects like Khomchalat’s Wongphai, which utilises biochar to support local bamboo ecosystems, are gaining attention alongside research-driven initiatives and pilot programs on other biochar utilisations. NGOs, young farmers, and policymakers are increasingly exploring biochar’s potential. According to BCHAR, the sector already enjoys strong support from government agencies, civil society organisations, and private-sector players.

However, Thai-led initiatives, says Pearl, often face a different reality. Many local founders report limited institutional backing, such as startup grants or R&D funding, prompting them to seek partnerships and financing abroad. While this creates additional pressure, it also means Thai-led models are often built without subsidy—making them more resilient and market-responsive over time.

Thailand's Barriers

Despite encouraging momentum, Thailand’s biochar sector continues to face six primary structural barriers that hinder widespread adoption:

Policy lag

Although policymakers are showing growing interest in low-carbon farming initiatives, comprehensive frameworks recognising biochar as a carbon removal methodology remain underdeveloped2. Khomchalat emphasises that tangible success stories—such as those emerging from Wongphai—are essential to spur financing, innovative funding mechanisms and favourable regulations.

Additionally, Pearl argues that coordinated financing mechanism are still missing to move from pilot projects to landscape-scale implementation. Current green finance tools often fall short when it comes to verifying impact at the scale banks and investors require.

Public awareness

Similar to what we saw in India, knowledge gaps exist at multiple levels—from farmers unfamiliar with biochar’s benefits to policymakers unaware of its climate mitigation potential3. Khomchalat and his colleagues from Wongphai address this through hands-on workshops designed to make biochar education practical and accessible.

Pearl has worked with many farmers that are already aware of biochar’s benefits and are actively seeking alternatives to chemical inputs. The real constraint for them lies in production and distribution capacity, which has yet to scale to meet smallholder demand, she says.

Farmer Skepticism

Darius notes that many farmers remain cautious about integrating biochar into traditional farming practices due to uncertainty about its long-term value: “Farmers need trust and affordability, which are not a given at the moment. Farmers often struggle to make ends, so why invest in the future if the present is uncertain?” This lack of trust slows uptake despite evidence of its benefits. Beyond trust, Pearl adds, it's also about economic feasibility. The average Thai farmer earns around $3,000 annually and often carries generational debt—making any upfront investment in new practices feel impossible. As Pearl puts it, “It’s not that farmers don’t care about the future. They care deeply—especially about their children. But without ecosystem support, change isn’t a choice. It’s a risk.”

Picture 4: Pre-treatment phase at BCHAR factory space

High Technology Costs

The upfront costs of pyrolysis technology remain prohibitive for smallholder farmers. Most systems currently used in Thailand are imported from China but are often ill-suited for local conditions. Nadja explains how BCHAR explores domestic production of Swiss-engineered systems tailored specifically for Thai needs.

Lack of Recognition in Carbon Markets

The BCHAR team points out that biochar is not officially recognised as a carbon removal methodology under Thailand’s bilateral climate agreements—a critical barrier for producers seeking access to international carbon finance mechanisms.

Enforcement Challenges

Although open burning is illegal in Thailand, enforcement on the ground is inconsistent—and often misunderstood. Pearl argues it's not just a matter of weak regulation, but of economic survival. Farmers, burdened by high input costs and stagnant crop prices, turn to burning as a fast and cost-effective way to clear fields. Without viable alternatives or meaningful transition support, burning remains the only feasible option for many. Local leaders, such as Subdistrict Headmen, are sometimes scapegoated in enforcement narratives, masking the deeper systemic challenges at play.

Picture 6: Wongphai project - collection and sorting of bamboo

Market Integration in Thailand

Grassroots initiatives such as Kon-Tiki kilns provide accessible entry points for smallholders but cannot meet growing demand for high-value biomass processing at scale (Puro.earth Carbon Removal Marketplace Overview). Khomchalat highlights Wongphai’s Pyrovine, which is an alternative pyrolysis technology that is under development. It is designed to serve as a promising ”bridging” technology that balances between artisanal community accessibility and industrial production capacity.

While agriculture remains the primary application due to its proven impact on soil health and crop yields4, other industries are beginning to explore innovative uses for biochar, including construction materials (e.g., SCG Cement) and animal feed applications. The former is taking the upper hand, according to Darius, as it is the most researched, most permanent, and most widespread biochar application apart from soil application.

Picture 8: BCHAR pyrolysis equipment

Thailand’s emerging biochar market reflects trends in other regions like India: grassroots approaches dominate early adoption while industrial-scale systems remain aspirational due tohigher capital requirements. Platforms like Happy Ground are helping bridge this gap through digital insetting models that connect farmers and corporations. By using field data to forecast yields, soil health improvements, and reductions in nitrogen fertiliser use, they align environmental and financial outcomes—turning Scope 3 emissions reductions into real farm-level impact. This isn’t charity; it’s a business case for regenerative supply chains.

Darius and Nadja note that while Thailand currently lacks national standards for biochar production or certification frameworks tailored to local contexts, this gap primarily affects accessibility for smaller producers. They stress that carbon removal standards should remain international and highly rigorous to ensure credibility and avoid greenwashing. In contrast, biochar applications—such as in soil or cement—can be locally regulated, provided they are grounded in science-based testing and aligned with existing quality standards, similar to how fertilisers or construction materials are governed.

Efforts led by IBAP aim to establish domestic standards that are aligned with international protocols while simplifying implementation for local producers3.

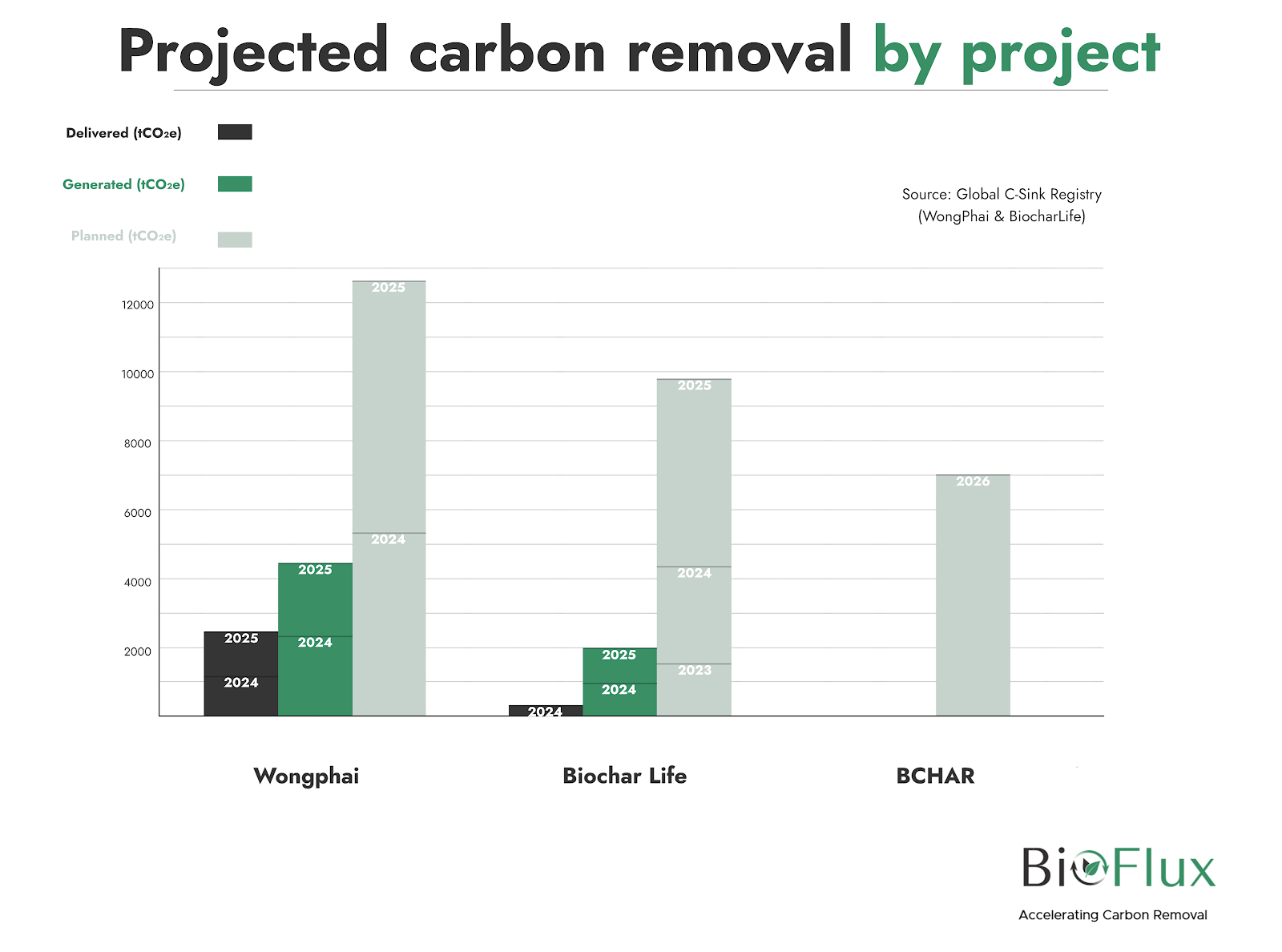

Picture 9: Output statistics per project

Biochar's future in Thailand

Khomchalat envisions advanced technologies driving Thailand toward becoming a regional leader in biochar production.

He emphasises three strategic priorities:

- Increased Investment - Enhanced funding mechanisms are critical for scaling production capacity.

- Clearer Regulatory Frameworks - Policies must differentiate pyrolysis from harmful agricultural practices like open-air burning.

- Education & Capacity Building - Raising awareness among farmers and policymakers is essential for effective adoption.

Darius and Nadja add that building independent supply chains will further strengthen Thailand's competitive advantage in biomass resources while enabling it to lead Southeast Asia's transition toward sustainable carbon removal solutions powered by biochar. They advocate for knowledge partnerships between government institutions and universities or other academic NGOs to allow success stories to step into the light. Showing Thai farmers the actual benefits through varioustrials is what will drive and unlock biochar in Thailand.

As Happy Ground’s founders emphasise, unlocking biochar’s full potential will require systemic coordination—not siloed projects. That means connecting actors across the entire value chain: from biomass collection and biochar production to farmer training, green finance, and corporate sourcing. If aligned properly, these systems can turn regenerative agriculture from a niche into the norm.

At BioFlux we're excited to see what the future will hold for biochar in Thailand. We expect IBAP to play a key role in aligning efforts with regional climate targets and amplifying Thailand’s leadership in biochar innovation across Southeast Asia.

In-text references

- United States of America, International Trade Administration; Thailand Country Commercial Guide, 2024 (link)

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH; ThaiCI Fund Empowers SMEs for a Low-Carbon Future, 2025 (link)

- Biochar Academy Thailand; Agenda, 2025 (link)

- The Nature Conservancy; Charcoal for Climate Action? New Study Advances Potential of Biochar from Crop Residues as a Climate Solution, 2023 (link)