The Distributed Model For Biochar Production

The Case for Distributed Biochar

As biochar carbon removal scales, a key question becomes whether decentralised systems can be deliberately designed to meet the expectations of large corporate buyers, insetting programs, and institutional investors without losing their local value creation.

Around 80% of farms in the Global South are smaller than two hectares (Lowder et al., 2021), and a significant share of rural households in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia live below national poverty lines (World Bank, 2024). At the same time, many of these regions face declining soil organic carbon (SOC), nutrient depletion, erosion, and increasing climate stress, undermining long-term productivity, resilience and general farmer livelihoods. Any carbon removal strategy that aims to integrate with agricultural supply chains must therefore engage smallholder systems as they are, particularly where soil degradation and livelihood vulnerability intersect.

In this context, decentralised biochar is less a philosophical choice and more a practical programme response. By stabilising carbon in soils, improving water retention, and supporting nutrient efficiency, biochar can contribute to rebuilding SOC while strengthening farm-level resilience. When linked to well-structured carbon finance, these soil improvements are not just environmental co-benefits; they become part of a broader income strategy that channels external capital into degraded landscapes and rural economies.

For capital to flow at scale into these landscapes, decentralised biochar programmes must be structured in ways that reduce delivery risk, measurement uncertainty, and governance fragmentation. Many early decentralised interventions have struggled not because of agronomic failure, but because they lacked aggregation mechanisms, consistent operating protocols, robust emissions monitoring, and clear accountability structures. From the perspective of a corporate buyer or institutional investor, dispersed production without disciplined programme design translates into high transaction costs, variable performance, and uncertain credit integrity. As a result, funding has often gravitated toward industrial facilities that offer simpler contracting and verification pathways, even when those models are geographically and socially less embedded.

Based on publicly available data published by CDR.fyi, decentralised production seems to accounts for less than 10% of traded volumes, compared to nearly 88% for industrial projects (CDR.fyi).

The implication for decentralised biochar is clear, it will not attract sustained capital flows on narrative appeal alone. It must be structured based on credible programme infrastructure. Across the sector, project developers, standards bodies, and MRV providers are beginning to converge on more structured approaches. Rather than asking whether smallholder systems can participate, the emerging question is how they must be organised to meet rising expectations around governance, traceability, and performance verification.

The Emergence of A Robust Distributed Model

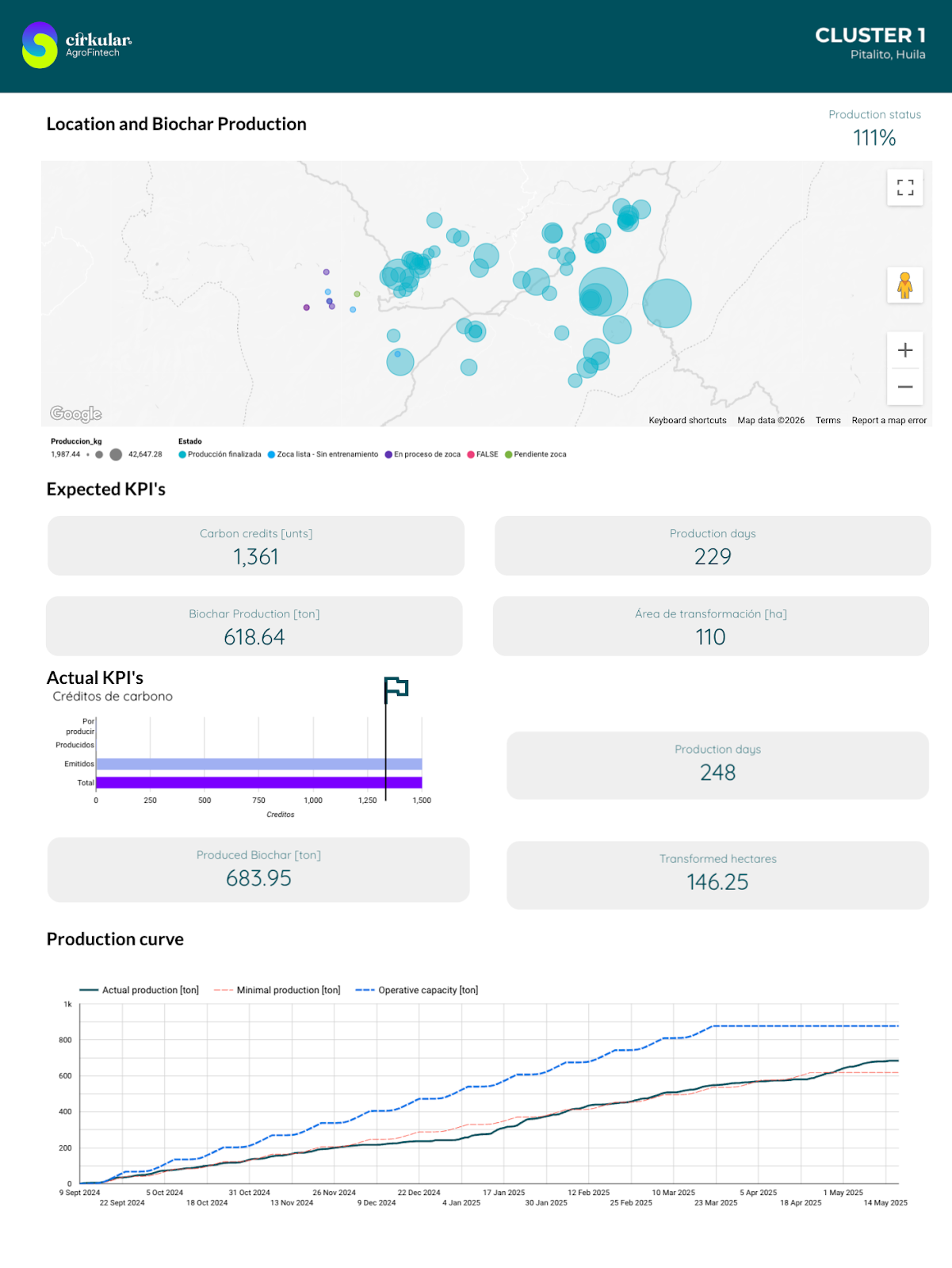

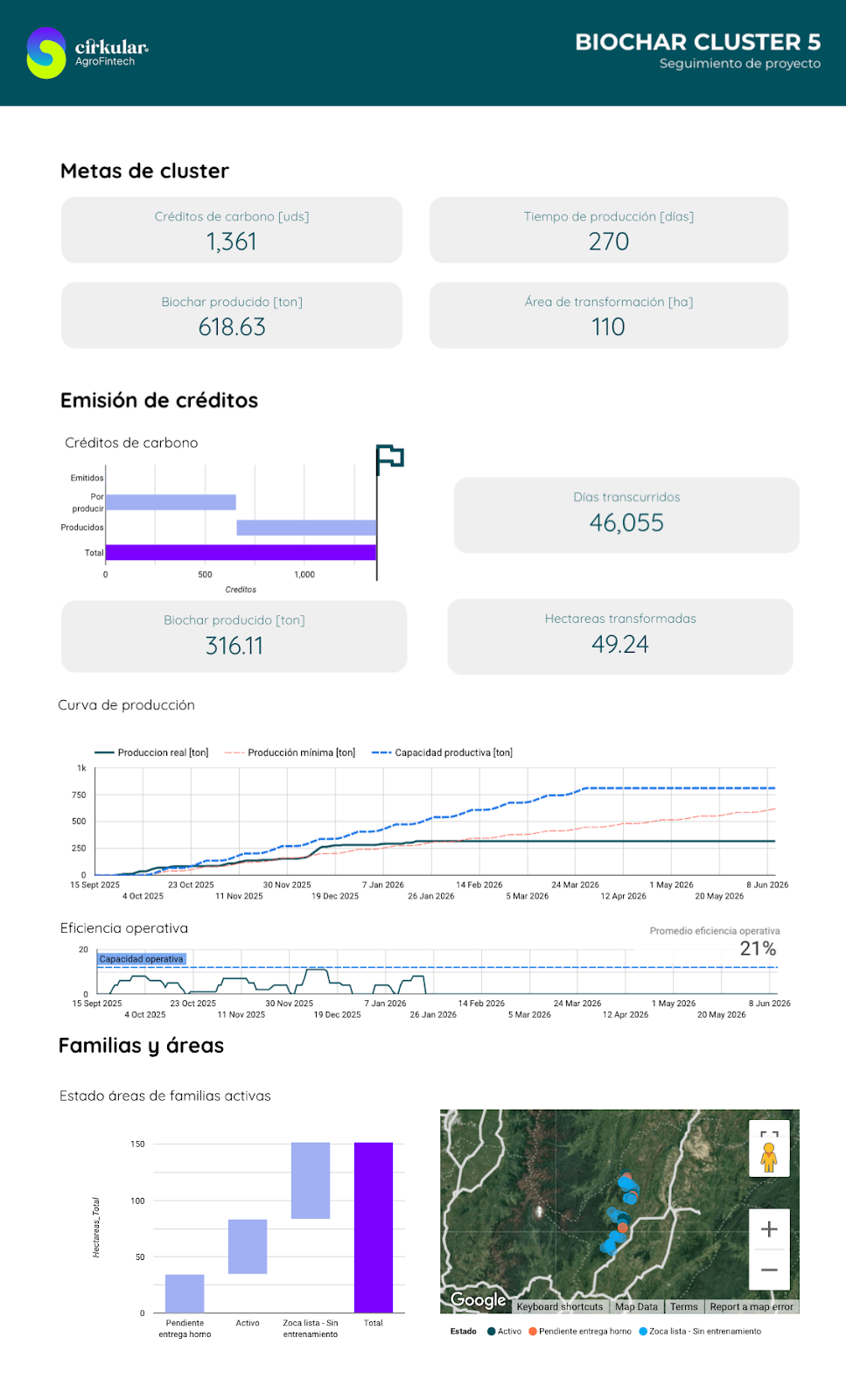

Over the past few months, we've observed and assessed innovations that have led, we would argue, to the development of a robust Distributed biochar production model.

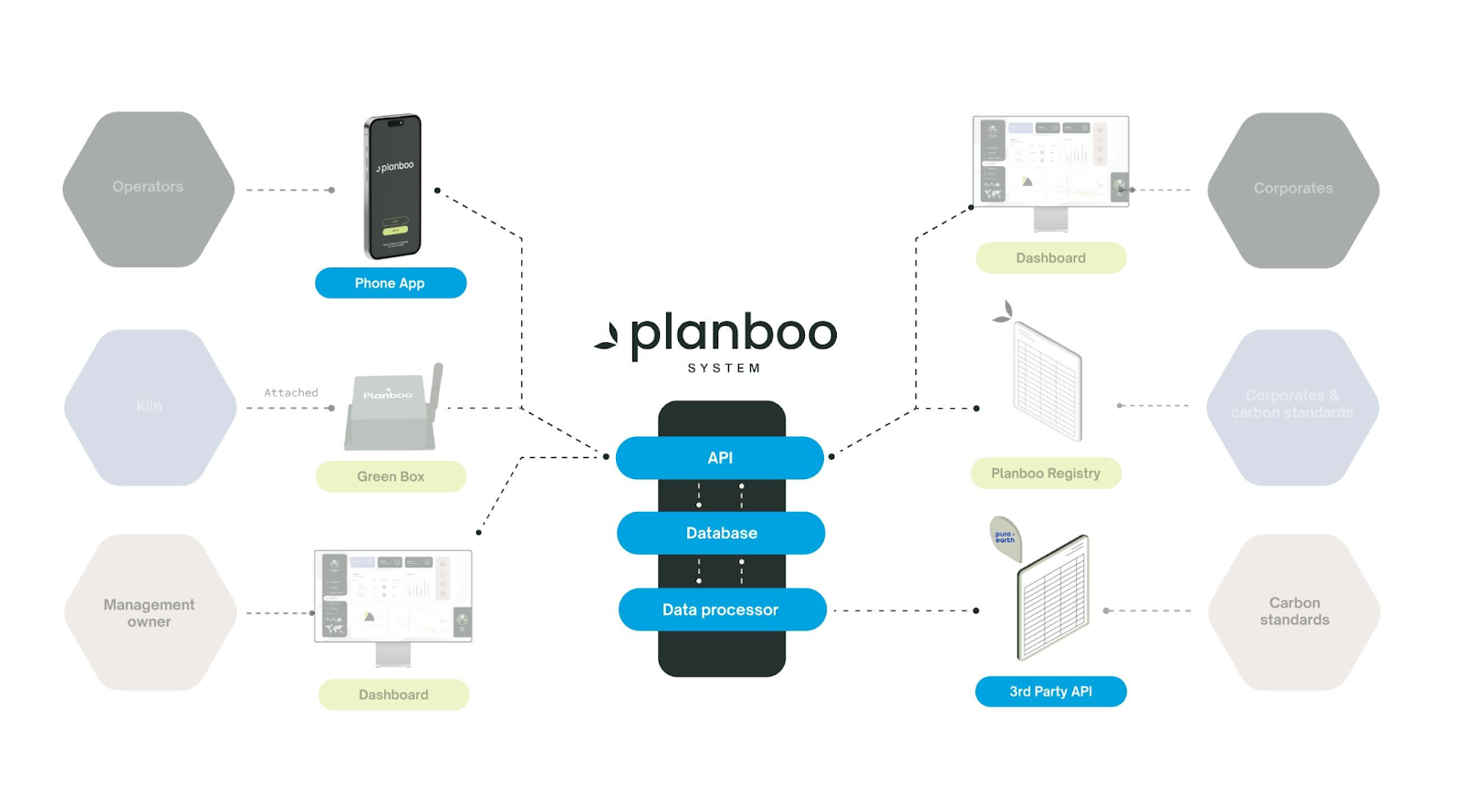

A farm-level biochar deployment method which retains the strong socio-economic benefits for farmers while resolving some of the pitfalls associated with artisanal biochar production. We're actively reflecting on the deployment models that suit this approach with project developers like Cirkular Origin, R3 Biochar, standards bodies including Isometric, Rainbow, and CSI, and MRV providers like Planboo and Circonomy.

This shift reflects broader industry efforts to professionalise decentralised systems through clearer governance, standardised operating conditions, and improved data capture.

These efforts are now beginning to materialise within formal carbon market frameworks, where standards bodies are updating methodologies to accommodate more structured distributed models.

Evolving Frameworks for Distributed Biochar

Recent standards developments reinforce this shift. Until recently, farm-level and decentralised biochar projects seeking carbon certification have had limited options, with CSI’s artisan methodology effectively serving as the primary recognised pathway. This is now beginning to change.

In early 2026, Isometric published a first, tightly scoped module for distributed, small-scale biochar production, representing an additional certification option for clustered, decentralised systems operating under defined governance and monitoring conditions. While this initial release is deliberately narrow in scope, Isometric has indicated that a broader version is already in development, intended to accommodate a wider range of distributed configurations and to more clearly differentiate professionally governed distributed models from traditional artisanal approaches.

In parallel, Rainbow Standard has recently opened a public consultation on updates to its core rules and procedures, signalling continued evolution in how decentralised and engineered carbon projects are governed and assessed. While not specific to biochar alone, this consultation reflects a broader move among standards bodies to clarify governance, verification expectations, and alignment with emerging integrity benchmarks.

These developments also signal that distributed biochar is no longer methodologically limited to a single artisan framework (CSI’s Artisan Methodology), but is entering a phase of methodological diversification, with additional pathways emerging.

Buyers and investors increasingly favour suppliers who can provide digital, auditable proof of impact from feedstock to end-use, putting immediate pressure on smallholder-based projects to professionalise; with robust MRV systems, clear governance, and tightly managed production and application practices.

These evolving standards frameworks do more than expand certification options; they clarify the structural expectations that distributed systems must meet in order to compete for institutional capital.

Combining strong community benefits with scalability

The Distributed model addresses the traditional tension between local impact and market viability by converting dispersed smallholder production into structured programme infrastructure. Rather than treating farmers as isolated micro-producers, it organises production into governed clusters, applies standardised operating parameters, and centralises monitoring and accountability at programme level. This shifts the risk profile from fragmented and transaction-heavy to coordinated and auditable, improving delivery reliability and performance transparency, both of which are critical for institutional carbon market capital deployment. In doing so, it creates a pathway for climate finance to enter dispersed agricultural systems without diluting oversight, integrity, or fiduciary controls.

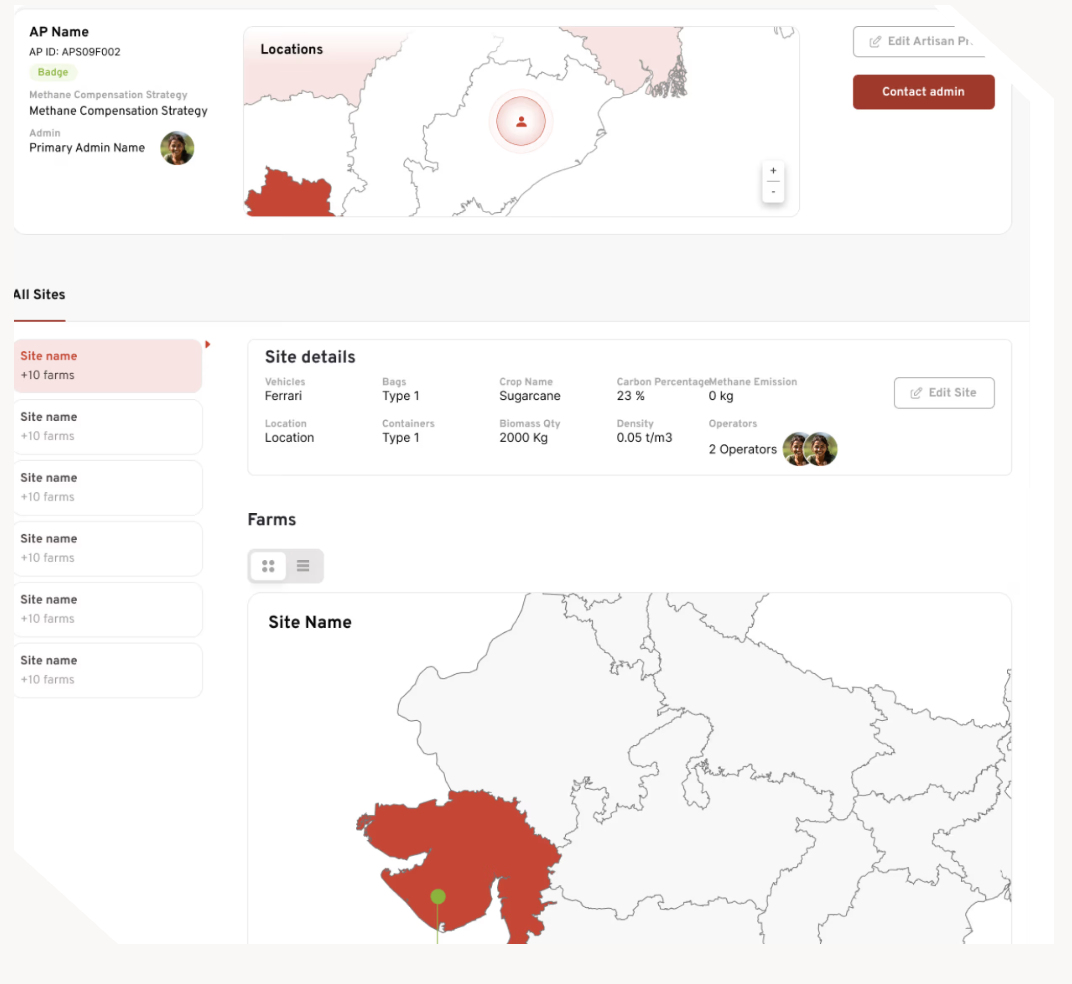

Project developers function as programme-level coordinators and counterparties to the carbon market, they choose and deploy reliable technology, enforce operating parameters, manage data integrity, and structure revenue flows - creating a single accountable entity capable of withstanding third-party audit.

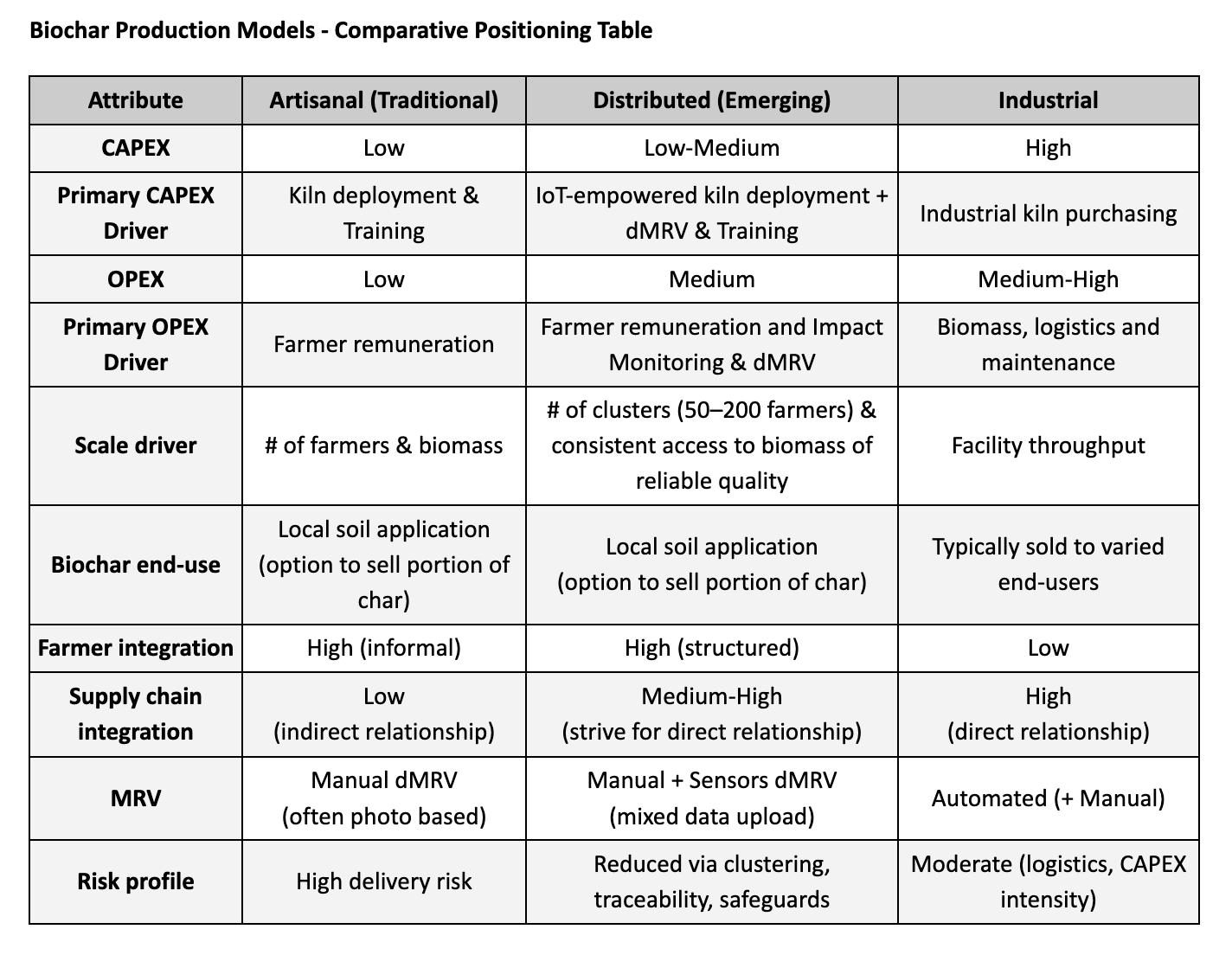

The distinction between artisanal, distributed, and industrial models is ultimately a question of where coordination, compliance, and monitoring responsibilities sit. The table below highlights how these responsibilities, and therefore risk profiles, differ across production structures.

What distinguishes Distributed Pro from traditional artisan approaches?

In the distributed model, biochar is produced through regional clusters of smallholder units that all follow the same robust technology, operating rules, and strict monitoring protocol. The emphasis is on consistent quality and verifiable performance across many small sites, rather than on building a few very large plants.

The goal is to build credible, replicable models following a clustered project approach, ensuring a project’s impact can scale credible without losing the direct farmer relationships needed for credible carbon, and beyond carbon impact, nestled in decentralised agricultural supply chains. In practice, credibility depends on the extent to which production is professionalised, monitored, and governed to integrity thresholds comparable to those applied in industrial contexts.

- Clustered production

In a distributed model, 50–500 farmers are organised into clusters, each treated as a single operational unit with shared feedstock planning, standardised practices, and a defined governance structure. Rather than operating as dispersed micro-projects, clustered production centralises coordination and establishes a clear point of accountability for monitoring, reporting, and delivery.

This structure pools operational risk, stabilises feedstock supply, and harmonises production protocols across sites, making performance more predictable over time. It also enables aggregation of credit volumes at a scale relevant to institutional buyers, reducing transaction costs and simplifying contracting. From a credit purchaser’s perspective, clusters convert thousands of small, heterogeneous activities into a limited number of structured units with defined oversight, clearer liability boundaries, and a more transparent risk profile, attributes that are central to long-term offtake and portfolio integration.

- Endorsed production technology

Traditional farm-level systems often rely on open or manually managed kilns where combustion efficiency depends heavily on operator skill. In response, newer distributed models are moving toward more enclosed, controlled kiln designs that aim to combust pyrolysis gases more consistently and reduce variability across batches. By limiting uncontrolled oxygen flow and reducing reliance on manual intervention, these systems seek to deliver more stable production metrics while remaining affordable enough for farm-level deployment.

Many of these designs undergo third-party validation for biochar quality and emissions performance, strengthening confidence in both carbon outcomes and process integrity. In addition to improving emissions control, including reductions in methane and smoke, more controlled combustion environments also enhance worker safety by reducing exposure to heat and harmful fumes.

- Robust digital monitoring

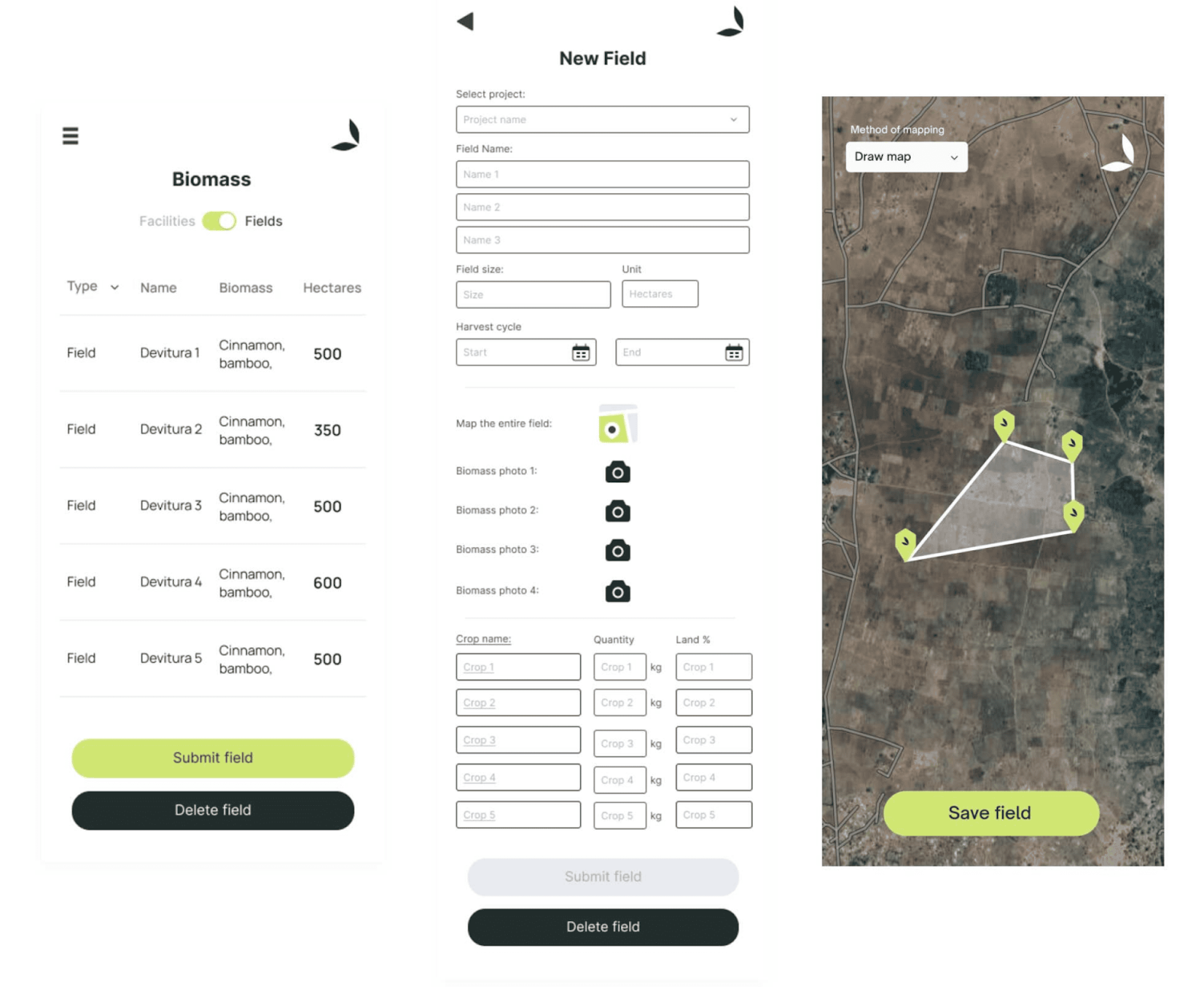

Traditional decentralised systems typically rely on basic documentation such as batch records, moisture readings, and time-stamped, geo-referenced uploads. More advanced deployments, however, seek to capture real operational data: including temperature curves, production logs, and in some cases direct measurement of methane and other process emissions.

By shifting from proxy-based reporting toward measured performance, these systems improve emissions accounting, reduce variability concerns, and provide the audit-ready transparency institutional buyers increasingly require.

- Structured farmer integration

Distributed programmes formalise farmer integration through structured participation agreements, documented training protocols, and transparent revenue allocation mechanisms. The goal being to capture verifiable data on training completion, production volumes, revenue distribution, and inclusion metrics; enabling third-party audit of both carbon performance and social outcomes.

This governance layer allows community-level benefits to be measured, attributed, and reported in alignment with living income benchmarks, supply chain sustainability commitments, and impact reporting standards. In doing so, it strengthens the credibility of livelihood claims while reducing reputational and compliance risk for downstream buyers and financiers.

- Supply chain embedding

Beyond carbon monetisation, embedding biochar within existing supply chains positions it as a form of climate risk management. For companies pursuing insetting strategies, the value lies not only in generating removals, but in strengthening the resilience of sourcing regions exposed to drought, soil degradation, and yield volatility. When linked directly to established supply geographies and traceability systems, distributed biochar becomes part of supply-shed stabilisation rather than a parallel offset activity.

In this configuration, carbon finance supports both durable removals and long-term agricultural productivity, aligning climate claims with procurement realities and reducing the disconnect between sustainability targets and operational supply risk.

Quantified co-benefits

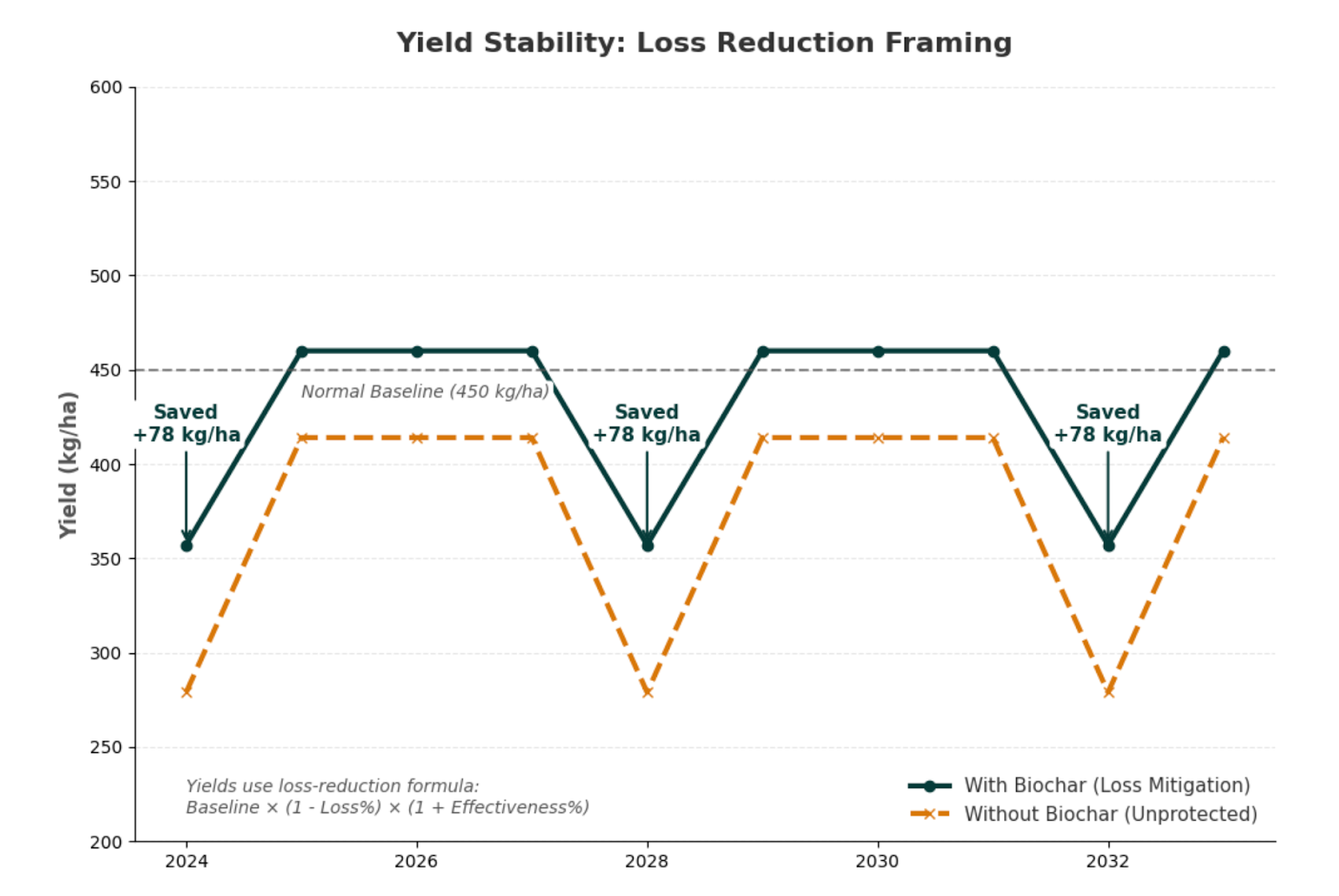

Distributed projects consistently demonstrate that biochar can support both livelihoods and climate goals. Multiple meta-analyses and field studies report average crop yield increases of around 10–20% after biochar application, with some contexts showing gains up to ~40–50% on degraded or nutrient-poor soils (e.g. Biederman & Harpole, 2013; Jeffery et al., 2011; Jiang & Li, 2024).

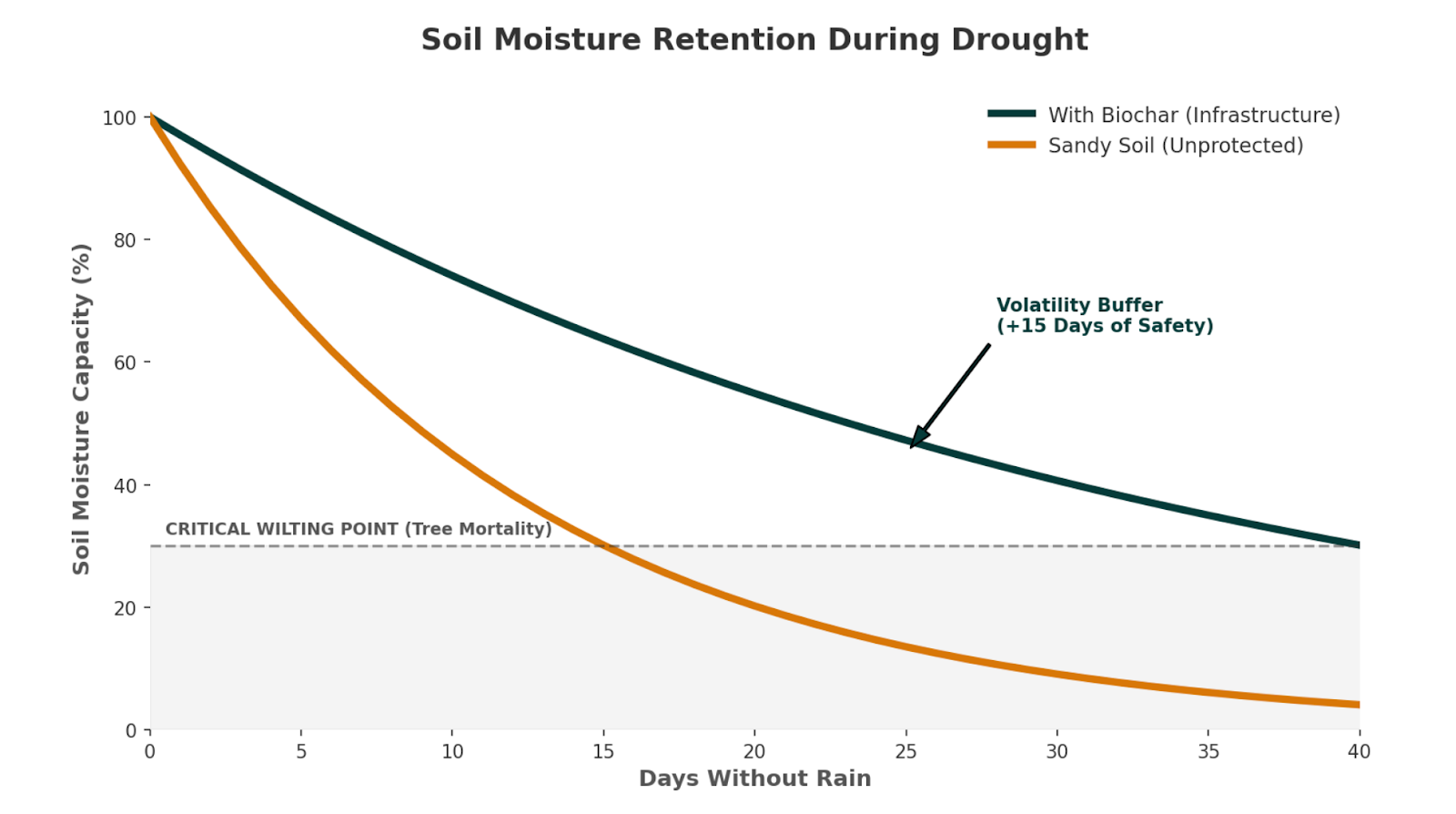

These studies also find improvements in soil organic carbon, cation exchange capacity, and water retention (El-Naggar et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2023). In practice, these agronomic effects translate into higher and more stable farm incomes, reduced fertilizer expenditure, and greater resilience to climatic shocks, while at the same time delivering durable, verifiable carbon removal.

Farmers benefit from additional income streams, reduced input costs, technology and knowledge transfer that strengthen local communities. At the same time, aggregating many small producers through clustered deployment creates credit volumes that move beyond pilot scale: regional programmes are designed to reach tens of thousands of tonnes of durable removals over a multi-year period, which is the level at which most corporate buyers and investors start to see distributed biochar as a serious, portfolio-relevant proposition.

Designing credible Distributed Biochar systems with BioFlux

As expectations around carbon integrity, verification, and accountability continue to tighten, biochar’s relevance will depend less on production scale alone and more on how systems are designed, governed, and evidenced in practice. Distributed biochar models can play a meaningful role in this transition, but only where they are structured to meet the same standards of credibility, traceability, and assurance increasingly applied across the carbon market.

BioFlux operates at this intersection: translating evolving standards, buyer requirements, and scientific constraints into practical system designs that enable biochar initiatives to remain credible, investable, and scalable over time. By focusing on governance, MRV, and value-chain integration rather than project ownership, BioFlux supports the development of biochar pathways that can withstand scrutiny while delivering durable climate outcomes and tangible benefits within agricultural supply chains.